It is important to remember the contributions of the people who came before us. Not only is it fair to give credit where credit is due, but for people who have struggled against racist and/or sexist limitations, seeing people break free of these constraints provides role models and hope. It shows that more is possible. The person to be remembered here is Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, an African American surgeon, who was one of the very first to perform a successful open-heart surgery in 1893 when surgery as we know it today was in its infancy. In addition to this groundbreaking surgery, he worked tirelessly in advancing the field of surgery in general and in increasing learning opportunities for other African Americans.

Daniel Hale Williams – Early Life and Education

Daniel Hale Williams was born on January 18, 1858, in Hollidaysburg, PA. He was one of seven kids, but after his father died, his family appears to have gone their separate ways. He ultimately went to live with the Andersons, an African American family in Janesville, WI1. They had three of their own kids, all of whom went into careers of medicine and dentistry, which was unusual at the time. It was there he met Dr. Henry Palmer, who was a Civil War veteran and surgeon, and Williams served as his apprentice from 1878 – 1880. Dr. Palmer was also a professor at Northwestern University, where Williams attended medical school, earning his MD in 1883. After a year-long internship at Mercy Hospital in Chicago, Dr. Williams began teaching at Northwestern University. This reinforced a strong foundation in anatomy, adding to his skill as a surgeon. Dailey, one of his contemporaries said, “his surgical work was marked by profound anatomical knowledge, a thorough understanding of physiology, normal and pathological, and an uncanny surgical judgment.”1

Dr. Williams Performs Open-Heart Surgery

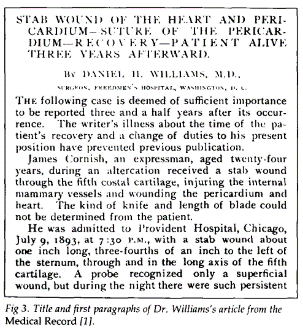

On 7/9/1893, James Cornish was stabbed on the left side of his chest during an argument and was admitted to Provident Hospital in Chicago2. Initially his wound was thought to be superficial, and he was observed overnight. However, the next day, it was discovered that Cornish’s pericardium (the tissue encasing the heart) was lacerated, and the heart muscle was punctured. Heart surgery was not an established field at the time, and it was thought that potentially fatal heart conduction problems could be caused by simple manipulation. However, on 7/10/1893, Dr. Williams closed the pericardium with fine catgut, a natural type of suturing material. Cornish remained in the hospital during his recovery, but on 8/3/1893, he appeared to be suffering from pericarditis with effusion (fluid). This can result from infection and/or inflammation and can be potentially life-threatening. Dr. Williams performed a pericardiocentesis, draining 80 ounces of fluid. Cornish was discharged from the hospital on 8/30/1893, and he lived until 19433, outliving Dr. Williams himself.

Dr. Williams published an account of this procedure in 1897, and for a time, it was thought that this was the first successful open-heart surgery because no other procedure had been recorded in the medical literature. Decades later, however, a woman name Helen Buckler wrote a biography of Dr. Williams, and through her research found that Dr. H. C. Dalton successfully performed a pericardial surgery in St. Louis in 1891, giving him cardiac operation priority3. However, that does not lessen the importance of what Dr. Williams did. “Here was a man called upon, without time for special preparation, to apply his surgical skill to a potentially fatal wound and about the most vital organ in the body. He did not hesitate, though he ventured where none had trod before.”4

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams – Other Accomplishments

Dr. Williams was ambitious and devoted to his profession. In 1891, he founded Provident Hospital, where the famous pericardial surgery took place two years later. This was the first US hospital to be operated by African Americans1. A school of nursing was set up with this hospital, which opened the doors to Black students, which no other schools in Chicago would allow at the time. The staff at Provident was mixed, and the patients were mostly white.

In 1893, Dr. Williams left Provident to become surgeon-in-chief at Freedman, where he transformed surgical services and established another nursing school. Before he arrived there, surgeries consisted mainly of amputations and simple superficial surgical repairs. Dr. Williams introduced new methods of sterilization, which allowed for more complicated surgeries. Dr. Warfield witnessed the transformation. He later wrote, “It can be said that surgical development began with the arrival of Dr. Williams, in all forms especially abdominal…. He was laying the foundation for more and better surgical work. By the time he left the hospital, in 1897 a great impetus had been given to all branches of surgery, except brain.”1

Another innovation that Dr. Williams brought to Freedman was to allow the public to view surgical operations one day per week. He was aware of how scary the thought of surgery was, and he was also aware that since Black surgeons were rare, the public did not have full confidence in them. By allowing the public to view operations, it demystified the process and showed people there was nothing to be afraid of4.

A Role Model for African American Doctors and Nurses

As might be expected, things were not always easy for Dr. Williams, and he seems to have harbored some resentments with Provident and Freedman. Regardless of the racial barriers he faced, Dr. Williams worked tirelessly to perfect his surgical expertise and to open the doors of medicine to other African Americans. In 1942, his colleague Dailey wrote:

“Dr. Williams’ practice knew no bounds of color, and for many years he had, in addition to that at Provident, a large private service at the St. Luke’s Hospital. More important than his vast surgical practice, his contributions to medical science, and his honors, was his role as inspiration and medical missionary to an entire profession. When Dr. Williams began practice, and for many years after, he stood alone as a surgeon. Many a Negro boy in the nineties and the early nineteen hundreds, owes to the name Daniel H. Williams, his inspiration and encouragement to study medicine. For a quarter of a century Dr. Williams made pilgrimages as lecturer and operator to the annual meetings of the Negro medical societies of the South and to the Meharry Medical College at Nashville. Here he not only taught scientific medicine and surgery by precept and example, but encouraged the founding of hospitals and training schools. His greatest pride was that, directly or indirectly, he had a hand in the making of most of the outstanding Negro surgeons of the current generation.”5

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams died in August of 1931 at the age of 73. His accomplishments were many, and he deserves to be remembered. He was someone who furthered the field of surgery through his commitment to excellence and constant effort to evolve. By opening teaching schools and being an educator throughout his life, he and opened the doors of the medical profession to people who had previously been barred from it. He is an example of how society benefits when individuals are able to develop their talents and become their best selves.

To read about more people unfairly overlooked in history, check out this article on Ignaz Semmelweis

REFERENCES:

1. Cobb WM. Medical History: Dr. Daniel Hale Williams. J Natl Med Assoc. 1953;45(5):379-385.

2. Olivier AF. In Proper Perspective: Daniel Hale Williams, M.D. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984;37(1):96-97. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(10)60721-7

3. Daniel Hale Williams Cardiac Operation Priority. J Natl Med Assoc. 1960;52(6):447-449.

4. Cobb WM. Daniel Hale Williams-Pioneer and Innovator. J Natl Med Assoc. 1944;36(5):158-159.

5. Dailey UG. The Negro in Medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 1942;34(3):118-119.